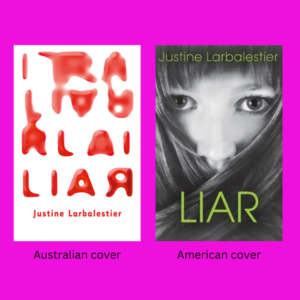

In 2009, Australian author, Justine Larbalestier, published her second novel, Liar. It is the story of Micah Wilkins, a 17-year-old pathological liar whose history of dishonesty comes back to haunt her at just the wrong time.

The book was well-received by Australian audiences and as Larbalestier’s publishing company prepared for a US release, they, like many other publishers, determined that a cover change was needed.

What began as an effort to authentically represent the book quickly shifted into a “do what sells” mentality resulting in a cover that couldn’t be further from the source material.

Though the new cover is a complete departure from the original, it still captures the essence of the book—but there’s just one problem:

Micah is biracial—African American and White. The description of her includes brown skin and short nappy hair. The author has even gone on record, stating she’d imagined her to look like WNBA player, Alana Beard.

WNBA player, Alana Beard

Despite these facts, the publisher felt it okay to go forward with the new cover, responding to Larbalestier’s objections with the excuse that “books with women on the cover sell;” conveniently leaving out the qualifier, White.

Readers were confused and rightfully upset by the change, and after much backlash, the publisher created a new cover.

Though not an exact representation of the protagonist, it at least came closer.

Whitewashing in publishing, (the act of using White people on the covers of books with non-white characters) is not a new phenomenon.

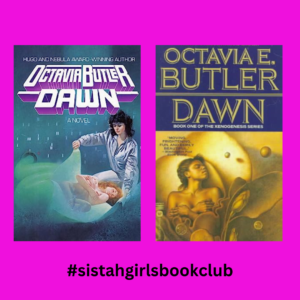

It happened in 1987, with Octavia Butler’s Dawn, in which the main character, Lilith Iyapo, is described as a “physically imposing Black woman with natural hair.” The cover on the right was not printed until 10 years later!

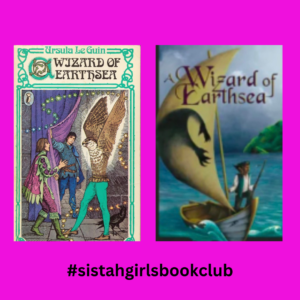

In 1988 (and subsequent editions) the cover of Ursula Le Guin’s, A Wizard of Earthsea featured whited-skinned characters when the majority of those in the novel are described as having dark skin.

And it persists today…

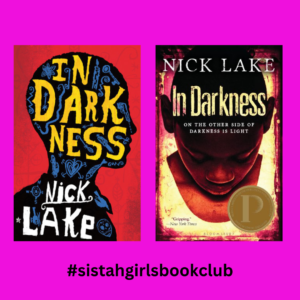

Nic Lake’s In Darkness is the story of “Shorty,” a 15-year-old boy trapped in a collapsed hospital during the earthquake 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

Initial printings offered a character in profile (another oft-used tactic) instead of using a Black person.

The American Gods novel has had several cover designs, but only the most recent one (inspired by the TV series) prominently displays the title character, who is of mixed race.

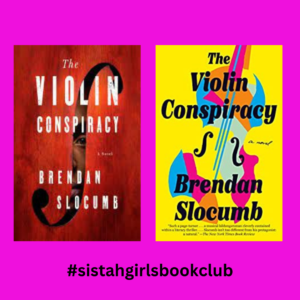

The paperback printing of The Violin Conspiracy replaces the Black man with imagery that while vibrant and eye-catching, does not match the tone of the story.

For years, publishing industry professionals have excused this erasure of Black faces and the limited representation of Black stories in the market with the unvalidated reasoning that Black books don’t sell.

It’s long been assumed that the lack of sales is because either Black people won’t read them, or White people “can’t relate” and thus won’t buy them.

And while at a time, that may have seemed true for some books, it might be more accurate to say that Black centered stories did not—do not—sell because they aren’t promoted with the same energy as their white counterparts; unless they’re written by White people, which is a whole other post…

How then, can readers purchase books if they don’t know they exist?

And if said books also have whitewashed or ambiguous imagery on the covers, how will the intended audience know those books are for them?

Whitewashing is harmful because it suggests that Black people aren’t enough to represent their own stories. That images of us aren’t attractive enough for the white audience they assume to be purchasing most books.

It also creates confusion amongst readers and may cause them to question the motivation and credibility of the author.

Ultimately though, it can cause the erasure of Black stories. If a reader sees a White person on the cover but comes across a description that paints the character Black, they may be inclined to see that as a mistake and continue interacting with the story as if the character is White.

Change Gon’ Come?

After the 2020 murder of George Floyd, people took to the streets in protest, but they also flooded bookstores. Titles like How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi, and Ijeoma Oluo’s So You Want to Talk About Race flew from the shelves and up the New York Times Best Seller list.

And while this led to increased visibility for all Black books and authors, it also, inevitably, brought out those who sought to cash in on the diversity “trend.”

Enter Barnes and Noble, and author David Bowles who both thought it acceptable to put Black people on the covers of books that had little to no Black characters—think Netflix baiting you with Black characters as the main image for a show they’re only in for 5 minutes.

Their answer was to be performative rather than truly put their power behind making room for and highlighting Black voices.

On the surface then, it might appear as if we’ve entered a time in which the world has finally come to see what we’ve always known: Black stories matter.

The trouble is, I can’t help but wonder when this bubble will pop.

According to Publisher’s Weekly, book sales dropped 8.9% from 2021 to 2022. There is no data to show the percentage of Black-centered books affected, but a substantial drop might lead to the assumption that the heightened consumption of Black literature was a mere trend.

This is why now more than ever, it’s important for publishers to continue to acquire Black books and have Black people on the cover of books that are specifically meant to represent or cater to the experiences and perspectives of the Black community.

Here are a few reasons why:

Representation

We know the power and validity of our experiences, but placing Black people on book covers shows us that we are seen, and sends a powerful message that our experiences are valuable and worth being acknowledged.

Breaking Stereotypes

Historically, Black people have been underrepresented or misrepresented in all forms of media.

By featuring Black individuals on book covers, publishers can challenge stereotypes and combat racial biases. It can also help dispel harmful misconceptions by offering more positive and diverse portrayals of black experiences.

Broadening Perspectives

Black books aren’t just for Black people.

Many readers appreciate diverse perspectives and stories. Having a diverse range of book covers can signal inclusivity and pique interest among a wider audience.

Empowering Black Authors

Prominently featuring Black people on the cover of black books supports and empowers Black authors by recognizing their unique voice, talent, and cultural contributions.

It can also lead to increased visibility, and help address the historical underrepresentation of Black authors in the publishing industry.

We’ve seen many positive changes over the last few years including publishers and readers actively seeking out books from Black authors and other marginalized communities.

While it’s absolutely imperative that Black people be featured on the covers of Black books, perhaps the most impactful thing publishers can do is commit to continually acquiring, highlighting, and promoting Black stories.

This will benefit readers of all backgrounds and foster a more equitable and inclusive literary landscape.